Episode 76- Can we treat bacteremia with cephalexin?

Episode Summary:

Or any other beta-lactam antibiotic? Or do we have to use a fluoroquinolone or Bactrim? Find out on this week’s Pharmacy Consult episode.

Show Notes:

Key Points:

“Can we treat bacteremia with cephalexin?”:

– Most studies found similar mortality and recurrent bacteremia rates with early step-down oral therapy compared to continued IV therapy for the treatment of bacteremia. Typically, patients had bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae (E.coli, Klebsiella) with urinary or GI tract sources of infection. They were also clinically improving and had already received 3-5 days of IV antibiotics

– The oral agent should have at least 90-95% oral bioavailability. Most experts recommend using fluoroquinolones (FQ) or Bactrim, but sometimes we have to choose an oral beta-lactam agent given allergies or other contraindications

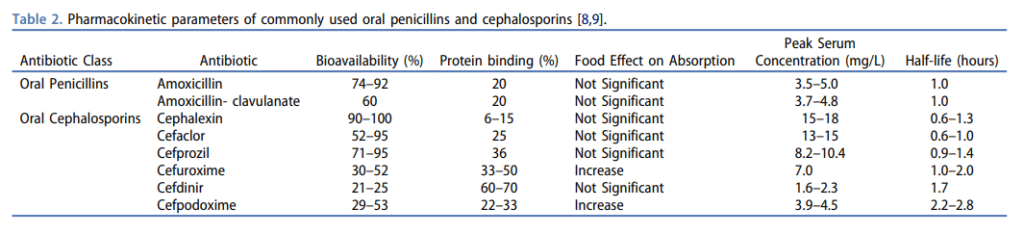

– Oral beta-lactams are typically considered “low bioavailability” agents, but that’s not always the case. Amoxicillin has up to 90% and cephalexin has reported almost 100% bioavailability– compared to some of the so-called “high bioavailability” agents like ciprofloxacin’s 70% and Bactrim’s 90% bioavailabilities (see chart below)

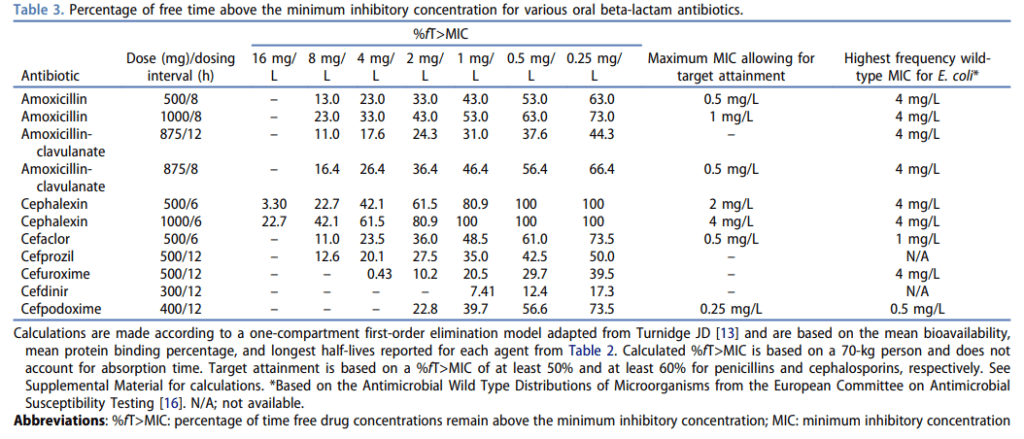

– Beta-lactam antibiotics are time-dependent killers, that require a drug concentration time greater than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 50% for penicillins and 60% for cephalosporins. We can achieve this by increasing the dose and/or the frequency of those agents. For example, amoxicillin should be dosed at 1 g Q8H and cephalexin should be dosed at 1 g Q6H when treating serious infections like bacteremia- provided that the MIC is low enough

– Most labs don’t report sensitivities to oral beta-lactams, in which case we can use the cefazolin sensitivity as a surrogate to predict sensitivity for the oral cephalosporins. Remember, that this surrogate only applies to treating uncomplicated UTIs caused by E.coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis– it shouldn’t be extrapolated to other infections, like bacteremia

– To get around this, we can use wild-type MIC distributions. For example the wild-type MIC occurring most commonly for cephalexin is 4 mg/L when we talk about E.coli, and in this case, cephalexin dosed at 1,000 mg Q6H can give you the best chance of reaching pharmacodynamic targets in a patient with normal renal function (see chart below)

– If treating a bacteremia with an oral beta-lactam antibiotic, consider using the usual 14-day treatment duration

Source: Mogle BT, et al. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019

Please click HERE to leave a review of the podcast!

Transcript:

Hello and welcome to Episode 76 of ER-Rx- a podcast tailored to your clinical needs. I’m your host, Adis Keric, and this week, we’re gonna talk about treating gram-negative bacteremia with oral antibiotics- specifically beta-lactam antibiotics, and even more specifically- cephalexin/ Keflex.

Switching to oral antibiotics can spare the patient from long durations of IV lines, can reduce healthcare costs, and can get them out of the hospital faster. Most studies found similar mortality and recurrent bacteremia rates with early step-down oral therapy compared to continued IV therapy – and typically these patients had bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae (E.coli, Klebsiella) and they typically had urinary or GI tract sources of infection.

The rule of thumb is that the oral agent you switch to for a bacteremia should have at least 90-95% oral bioavailability. Given this, most experts recommend using fluoroquinolones (FQ) or Bactrim. But sometimes bacteria are resistant to these agents, or patients can have allergies to them, or they can have other concerning comorbidities like CKD or a prolonged QTc that prohibits them from getting them. Sometimes we get stuck with having to choose an oral beta-lactam agent, and if that’s the case, which one should we use, and how should we dose it?

In 2019 a group of authors compared outcomes of patients who transitioned to either an oral FQ or Bactrim – typically referred to as “high bioavailability agents” – compared to patients transitioned to oral beta-lactam antibiotics- which are for the most part considered “low bioavailability agents”- but more on that later. They reviewed over 2200 patients with bacteremia caused by gram-negative organisms. 65% of patients were given an oral FQ, 8% were transitioned to Bactrim, and 27% were transitioned to an oral beta-lactam. All-cause mortality was not different between patients who got FQ/ Bactrim vs. beta-lactam antibiotics (~5% vs ~3%). But infection recurrence happened more often in patients who were treated with oral beta-lactams compared to FQs specifically (~5.5% vs ~2%)- there wasn’t enough data to look at outcomes of patients given Bactrim compared to beta-lactams. But the authors admit that beta-lactam regimens chosen for patients required high frequencies that could have led to poor compliance or more importantly, and the topic of this episode, they just didn’t give a high enough dose.

And to clear something up, even though we put oral beta-lactams in the “low bioavailability” bucket, that’s not always the case. Amoxicillin has up to 90% and cephalexin has reported almost 100% bioavailability– compared to some of the so-called “high bioavailability” agents like cipro’s 70% and Bactrim’s 90% bioavailabilities. I’ll post a chart that you can refer to onto the ER-Rx Podcast Instagram page and on errxpodcast.com. But bioavailability isn’t the only thing we care about. Since beta-lactam antibiotics are time-dependent killers, we generally shoot for a drug concentration time greater than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 50% for penicillins and 60% for cephalosporins. Without nerding out too much, we can achieve this by increasing the dose and/or the frequency of those agents. For example, to optimize this, amoxicillin should be dosed at 1 g Q8H and cephalexin should be dosed at 1 g Q6H when treating serious infections like bacteremia- provided that the MIC is low enough. Which brings us to the next kicker: most labs don’t report sensitivities to oral beta-lactams. And if they don’t, we’re stuck with using the cefazolin sensitivity as a surrogate to predict sensitivity for the oral cephalosporins. The only bummer is that this surrogate only applies to treating uncomplicated UTIs caused by E.coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis- it shouldn’t be extrapolated to other infections, including bacteremias.

To get around this, we can use well-known, but not often reported, wild-type MIC distributions. For example the wild-type MIC occurring most commonly for cephalexin is 4 mg/L when we talk about E.coli, and in this case, cephalexin dosed at 1,000 mg Q6H can give you the best chance of reaching pharmacodynamic targets in a patient with normal renal function. This is another image that I’ll post on the Instagram page and on the website. Going back to that 2019 review, most of the patients transitioned to an oral beta-lactam were put on Augmentin, amoxicillin, or cephalexin—but doses varied widely with a lot of underdosing. Specifically, in terms of the cephalexin dose, all patients received 500 mg Q6H- and not one patient received the necessary 1,000 mg Q6H dose. And this is probably why patients transitioned to oral beta-lactams like cephalexin had more infection recurrence.

I know that was a lot, so let’s wrap this up- in a patient with a gram-negative bacteremia caused by an Enterobacteriaceae, ideally with a urinary or GI source- consider completing the course with step-down oral antibiotic therapy – especially if the patient is clinically improving, blood cultures have cleared, and the patient has received at least 2-3 days of IV antibiotics. The oral agent you use should be a FQ or Bactrim—but we have more and more evidence showing that using an oral beta-lactam can work just as well. Just make sure you’re selecting the one with high bioavailability and that the dose is high enough to optimize pharmacodynamics by using charts like the ones I’m going to post online.

And just one more final thought: although there is more and more data coming out that 7 days can be considered an adequate duration for these uncomplicated bacteremias, I would still personally use the usual 14-day duration if I’m switching to an oral beta-lactam- just to make absolutely sure the infection clears. Discuss the importance of strict compliance with the high dosing frequencies and return to the hospital if the patient doesn’t improve or if they get worse. This is all super complex stuff so if you’re listening and this isn’t making sense—please talk to an ID pharmacist or an ID provider prior to doing this.

As always, thank you so much for your time, and thank you for wanting to learn more about pharmacotherapy. If you have any comments or anything else you’d like to add to this, or any other episode, please reach out to me — I’d love to respond to all comments and criticisms. Also, please remember to leave a review of the podcast so that more of our colleagues can find the show on Apple Podcasts. And if you can afford it- please consider donating to the show to help keep it free for everyone. Links to both leaving a review and donating are found on the Show Notes and they are both super easy to do. I appreciate all of you guys and I’ll see you next time.

References: