Episode 57- Escaping “SCAPE”

Episode Summary:

This week, we discuss the use of noninvasive ventilation and high dose nitroglycerin to prevent intubation in patients with SCAPE

Show Notes:

Key Points:

“Escaping ‘SCAPE'”:

– Hypertensive acute heart failure (AHF) causes an increase in afterload and a decrease in venous capacitance which shifts fluids into the pulmonary circulation. A severe form of hypertensive AHF is “sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema” (SCAPE) or “flash pulmonary edema”

– Vasodilators plus noninvasive positive pressure ventilation has been described as a treatment for SCAPE. In this case nitroglycerin (NTG) is the vasodilator of choice, and higher doses (50- 250 mcg/min) are needed to dilate the arteries and reduce afterload. Noninvasive ventilation should be used in conjunction with high dose NTG to reduce preload and afterload, improve symptoms, and prevent intubation

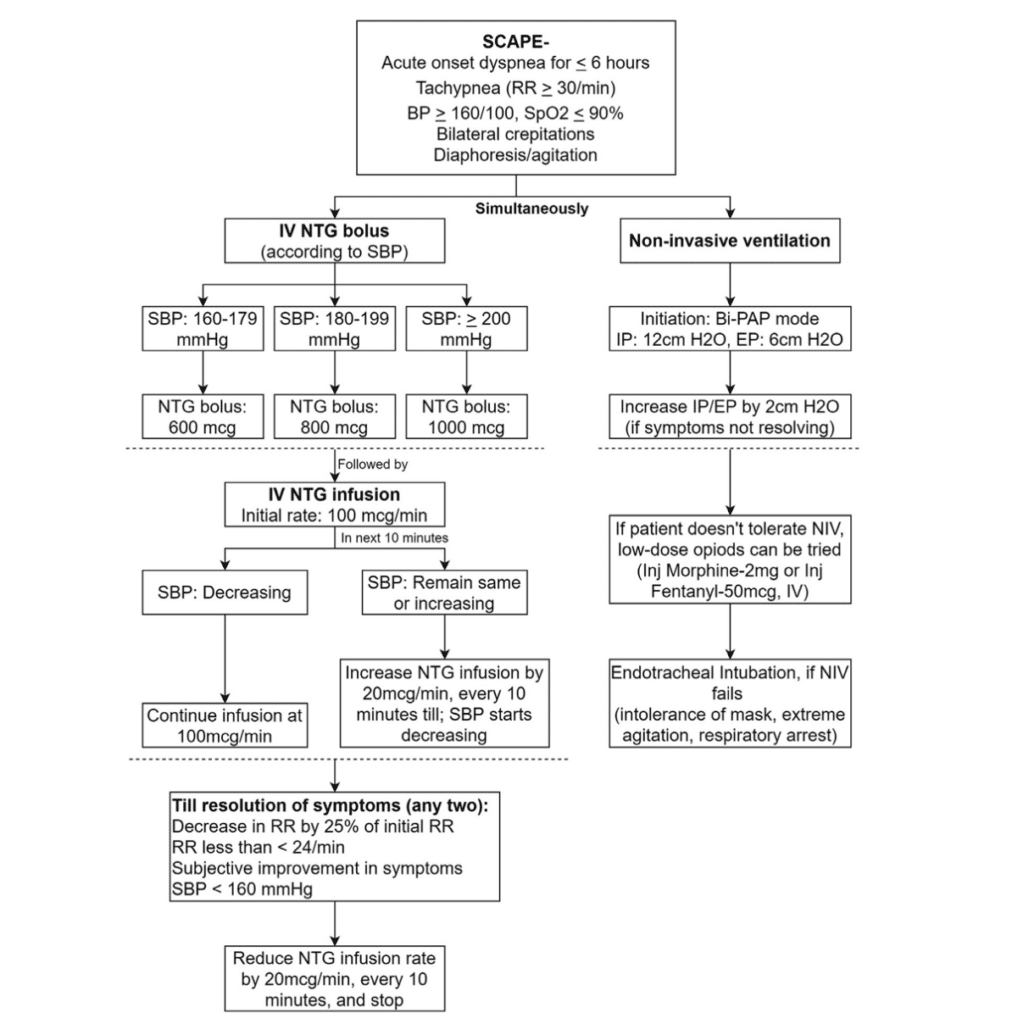

– In this prospective observational study, the authors defined SCAPE as an acute onset of dyspnea (</=6 hours), tachypnea (RR >/= 30/ min), hypertension (BP >/= 160/100), hypoxia (SPO2 </= 90% or < 95% on oxygen), bilateral crepitations, and diaphoresis/tachycardia/agitation that is associated with sympathetic surge. Patients were then started on noninvasive ventilation with inspiratory pressures of 12 (cm H20) and expiratory pressures of 6 (cm H20), titrating by 2 (cm H20) if needed and proceeding with intubation if this failed

– At the same time, patients were given a NTG bolus between 600-1000 mcg depending on their blood pressure and they were then started on a NTG infusion at 100 mcg/min. The NTG was titrated by 20 mcg/min every 10 minutes until there was a trend in decreasing blood pressures and it was continued until resolution of symptoms. In patients who improved, the NTG infusion was reduced and they were given their home anti-hypertensives, or they were started on anti-hypertensives in the ER (in this case, they used an ARB). See the image below

– They enrolled 25 patients, the mean age was 44 years and about ~1/2 of the patients were male. The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (76%), CKD (60%), and diabetes (40%). Noninvasive ventilation was started as per protocol and 6 patients reached the maximum inspiratory pressure of 16 (cm H20) and expiratory pressure of 10 (cm H20). The mean NTG bolus was 872 mcg and the maximum rate of infusion required was 200 mcg/min. There was no incidence of hypotension with the bolus dose, but 2 patients did develop hypotension with the continuous infusion that was responsive to a fluid bolus. Only one out of the 25 patients required intubation, with the rest of the twenty-four patients discharging home

Source: High-Dose Nitroglycerin Bolus for Sympathetic Crashing Acute Pulmonary Edema: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021

Please click HERE to leave a review of the podcast!

Transcript:

Hello and welcome to Episode 57 of ER-Rx. This week, we discuss a recently-published article from the Journal of Emergency Medicine entitled “High-dose nitroglycerin bolus for sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema: a prospective observational pilot study.”

Hypertensive acute heart failure (AHF) is associated with an increase in afterload and a decrease in venous capacitance which shifts fluids into the pulmonary circulation. A severe form of hypertensive AHF is “sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema” (SCAPE) which is also known as “flash pulmonary edema”. Patients with SCAPE have a rapid onset and progression of respiratory symptoms (tachypnea, use of accessory muscles, or orthopnea) and hallmark sympathetic surge leading to vasoconstriction and increased afterload. Given the hyperacute presentation, rapid identification and treatment in the ER is a must to prevent symptomatic worsening and subsequent intubation.

The use of vasodilators and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation has been described in the literature as a treatment for SCAPE in the ER. Vasodilators work by reducing preload and afterload to relieve pulmonary congestion. In this case nitroglycerin (NTG) is the vasodilator of choice. Remember that lower doses (< 50-100 mcg/min) of IV NTG mostly affect veins and higher doses (> ~100 mcg/min +) are needed to hit the arteries. In the setting of SCAPE, we need higher doses (50- 250 mcg/min) to dilate the arteries and reduce afterload. Along with NTG, noninvasive ventilation is highly recommended for acute pulmonary edema and should be used in conjunction with high dose NTG to reduce preload and afterload, improve symptoms, and prevent intubation.

In this prospective observational study out of India, the authors developed a SCAPE treatment protocol that included high-dose NTG and noninvasive ventilation and then they assessed the feasibility and the safety of that protocol. They defined SCAPE as an acute onset of dyspnea (/= 30/ min), hypertension (BP >/= 160/100), hypoxia (SPO2 At the same time, patients were given a NTG bolus between 600-1000 mcg depending on their blood pressure and they were then started on a NTG infusion at 100 mcg/min- notice the use of a bolus dose and the relatively high starting rate of NTG—in this setting starting at our usual angina or heart failure exacerbation dose of 10-20 mcg/min is not even close to enough. The NTG was then titrated by 20 mcg/min every 10 minutes until there was a trend in decreasing blood pressures and it was continued until resolution of symptoms. In patients who improved, the NTG infusion was reduced and they were given their home anti-hypertensives, or they were started on anti-hypertensives in the ER (in this case, they used an ARB). For a visual, I’ll post the full protocol onto errxpodcast.com and the @errxpodcast Instagram page.

They enrolled patients who were > 18 years old who met the diagnosis of SCAPE. Patients were excluded if they required intubation or CPR, if they had a contraindication to NTG (allergy, aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, use of sildenafil within 24 hours or tadalafil within 48 hours), or if they had ACS. The protocol was stopped if patients developed bradycardia (HR < 60), new onset chest pain, or new neurologic deficits.

In the end, they enrolled 25 patients- remember this was a small pilot study. The mean age was 44 years and about ~1/2 of the patients were male. The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (76%), CKD (60%), and diabetes (40%). Noninvasive ventilation was started as per protocol and 6 patients reached the maximum inspiratory pressure of 16 (cm H20) and expiratory pressure of 10 (cm H20). The mean NTG bolus was 872 mcg and the maximum rate of infusion required was 200 mcg/min. There was no incidence of hypotension with the bolus dose, but 2 patients did develop hypotension with the continuous infusion that was responsive to a fluid bolus. Impressively only one out of the 25 patients required intubation, with the rest of the twenty-four patients discharging home.

Despite the limitations of having low numbers and being a single-center pilot study, the authors concluded that the use of a standard SCAPE protocol resulted in rapid resolution of symptoms and was well tolerated. They stand by their NTG dosing scheme using a bolus followed by a continuous infusion starting at 100 mcg/min. There are other ways of administering NTG. For example, in another study they withheld the bolus dose and just started a NTG infusion at 400 mcg/min and then reduced the dose by 50 mcg/min every 5 minutes as tolerated. Other authors recommend giving 400 mcg/min for 2 minutes, then titrating back to 100 mcg/min. Whichever way you do it, remember that doses tend to be pretty high.

In terms of the loading dose, others have given 0.5-2 mg – yes milligrams- IV boluses every 3-5 minutes, with some starting a NTG infusion after the bolus and others just using bolus dosing as needed. All these high doses can potentially make some providers, pharmacists, and nurses uncomfortable- and understandably so. But as long as you have the correct diagnosis and as long as you are at the bedside frequently monitoring your patient, you should see very rapid improvement with the ability to wean the NTG off pretty quickly with a very low risk of hypotension. You may be asking yourself why diuretics aren’t included in this protocol. A good thing to remember is that in the setting of SCAPE, most patients are euvolemic, and sometimes even hypovolemic, and they usually don’t need IV diuretics in the acute management phase in the ER.

In conclusion, remember that SCAPE requires immediate recognition and treatment. Starting noninvasive ventilation with high dose NTG has been shown to lead to better outcomes and less intubation with very low risks of hypotension. Following a protocol like the one discussed in this article could help you manage these patients in your own practice.

As always, thank you so much for your time. Please remember to share this podcast with a medical nerd in your family, and please subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Podchaser, Amazon Music, or wherever else you get your podcasts. Remember subscribing is free and you’ll get automatic updates any time a new episode is released. See my show notes on how to how to do this.

References: